Setting Sail for the Faroe Islands, 1st – 3rd September 2025

After a lunch of quinoa with feta cheese, we set about getting the yacht ready for departure. The sail covers needed taking off, the fenders positioned appropriately for casting off, and we needed to reposition the mooring ropes so that we could slip them from the boat.

Before casting off, we held our first Man OverBoard (MOB) exercise, which was ‘dry’ – ie. while the boat was moored, and without a ‘wet’ casualty to pick up. Jess stepped up to be the rescue person, putting on a Fladen dry suit with a harness attached to red and green ropes from the top of the mast.

She was lowered off the side of the boat in a harness to rescue an imaginary casualty with Lynne and Andrew easing the lines on the winches, in tandem, to lower her gently down to sea level, where she would have hooked onto the casualty in the sea, and both been winched up to safety by Lynne and Andrew.

Lynne went ashore to help with preparing the ropes to cast off. Now she faced a fleeting moment of indecision: should she really choose to step aboard and head into the storm?

Finally we left the sheltered mooring of the small harbour at Seydifjordur in the low cloud at 4.25pm. First, our sister boat, Hummingbird, left, shortly followed by Bluejay. As we approached the end of the fjord, the seas became more lusty, as we set about hoisting the sails. First, the main sail, then later the yankee, and finally the stay sail forwards of the mast. We would be sailing for 52 hours to Klaksvík in the Faroe Islands. That would involve two nights at sea.

The nine paying crew were divided into three ‘watches’. Under supervision of the skipper or mate, we were to helm, look-out and manage the sails throughout the voyage – each watch having three hours on watch, three hours standby (available for duties, eg. cooking, cleaning, etc.) and three private hours (sleep!).

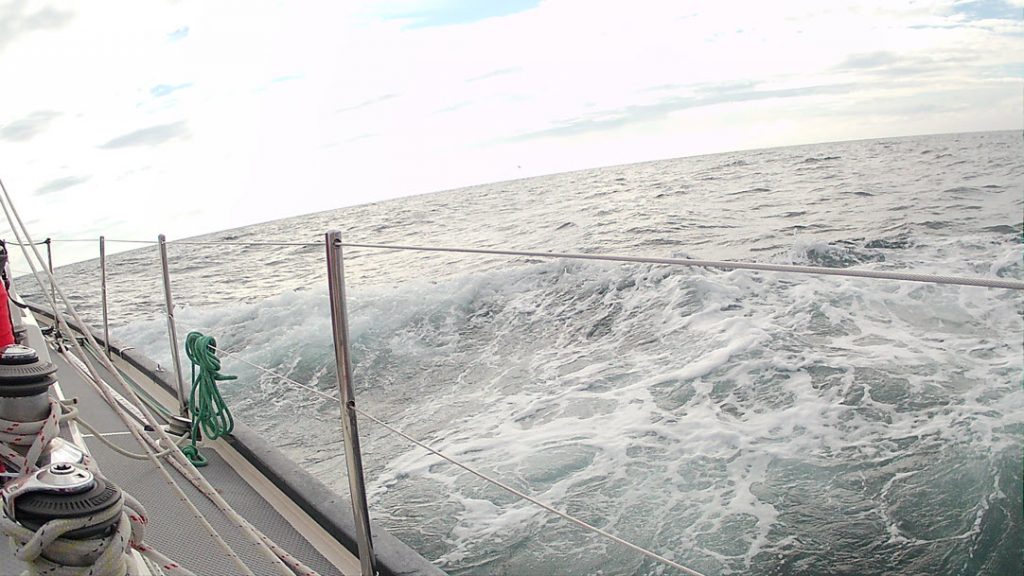

The passage from Iceland to the Faroe Islands was a blur. As we left Iceland behind, the already dark heavens, with scudding rainclouds, became murky, merging with the dark steel of the rushing waves. Visibility was poor. It was so much colder in the open cockpit than we had expected; we had brought enough warm clothes, but hadn’t really had the time to unpack and add more layers before setting off.

Bluejay headed off on a course of 120 degrees with North-Easterly winds approaching 16 knots, heeling under the pressure of the wind, bashing against the 2m swells. The wind speed increased to hover around 30 knots, near-gale conditions. The majority of crew felt affected by sea sickness – some felt queasy, some felt retchingly sick. Most just laid down on their bunk when not working. In the cockpit; the meaning of the blue bucket became clear, some clutching it desperately.

The best way to abate sea-sickness is by eating, drinking and looking at the horizon from the cockpit. Lynne made the error of going into the galley for a hot drink and biscuits to warm up. Big mistake: that caused her to keep throwing up and what without managing to locate her water bottle for 24 hours, meant she was incapacitated in her bunk for 48 hours, save for a couple of hours on-deck clutching the bucket. She only managed to eat a couple of crackers, an over-sized polo mint and sip water, unable to fulfil any crew duties at all.

The 3-hour duty watches were spent in the open cockpit, one on the helm, the other two bracing against the motion. It was cold, windy and wet, so we all had mutliple layers, including our foulies, lifejackets and three-point tethers. At least one of the tether clips had to connect to a safety eyelet at any time, so moving around, for instance to take over the helm, became an interesting game of not tangling while moving from eyelet to eyelet.

Nighttime was red light time, with all below deck lights either off or red. On-watch crew needed to have red headtorches if anything needed doing on the winches or clutches. Peter had temporarily lost his headtorch among the chaos of unpacking at Seydifjordur, with Andrew gallantly lending him his at one point.

Helming was the scary bit. Skipper or Mate, stood by to make sure the helmsman knew what she/he was doing, but when satisfied, just left the job to the helmsman. In daylight, it was daunting. We were given a course – 210 degrees – the binnacle had the gimballed compass, as well as a computer readout device, showing wind/sail direction information, ‘speed over ground’ (SAG), and windspeed. There was also a readout of sea depth, but that remained blank, as it was out of range…

Helming is nothing like driving a car. Absolutely not! The helm wheel is big, connected to the rudder below. The below surface seas were constantly shifting, currents, swells, waves, with the 35 tonnes of our boat slapping into the seas. Winds veered and suddenly gusted. It was a full time job to helm in rough seas. Mostly, each helm pass was for half an hour, but that was enough, as it was really hard work on arms and shoulders, while standing with wide legs, bracing against the sudden movements. With land in sight, one could steer towards a point, but on the open sea, only the compass was of help.

At night, helming was even more intimidating – one sensed the sea, white crests speeding by. One could feel the sails straining in the wind. The compass was dimly lit, glass dome covered in rain, crazily tilting as Bluejay crashed through the night. One wondered what to do if the compass light failed… Indeed, one’s mind worried, what if we were hit by a big gust? One felt the responsibility for all crew members, resting and sleeping below deck.

At the end of the watch, the new watch appeared in the companionway in their bright yellow foulies, carefully handing up hot drinks in the wonderful Yeti mugs. After gratefully finishing our drink, the job was to remove our tethered lifejackets and soaking wet foulies, while trying not to topple over in the dark vestibule. Climbing into the bunk was a blessing, despite the angle the bunk was at!

The bunk mattresses were nice and comfortable, with good pillows, but narrow, oh so narrow! Just wide enough for our sleeping bags – no room to spread out a bit! Apart from mattress and pillow, the most essential feature was the ‘lee cloth’, a piece of fabric attached to below the mattress and a string, the length of the bunk. We had understood that this was meant to give a little privacy, but we discovered that it was to contain any items – and person (!) – in the bunk while sailing. Completely necessary, we found, as people’s belongings were shaken out of bunks, skiting across the floor.

Our bunks

Lee cloths up

Indeed, when Lynne was ill, her lee cloth OXO-knot wasn’t secured tightly enough (Peter trying to be helpful), so that she was thrown out of her bunk, in her sleeping bag, under the lifejacket rail, ending up in a tangle by Colin’s bunk, helped back into her bunk by Colin and Jess, who calmly insisted she needed to climb out of her sleeping bag first!

Peter and Lynne’s bunks were on starboard side, so, when on starboard tack, the bunks were averaging an angle of 30 degrees – resulting in sliding sleeping bags. Most people held on by a combination of trusting the lee cloth and clinging onto the cold boat metal walls while sleeping. Blissfully, when on port tack, it leant the other way, so we were secure against the boat, but we didn’t experience that luxury on this part of the journey.

After Lynne fell out of her bunk, Peter was extra careful in securing his leecloth – falling out of the top bunk would not have been good. In fact, getting up and down to the top bunk was not straightforward. It required some acrobatics involving the rail for the lifejackets.

On the hull side of the bunks, there were holes in the metal wall, which provided the handy places to hang onto while trying to sleep, but also served to store our personal belongings. The space in the wall was under the upper deck gunnels, so had the sea just on the other side of the metal wall. This meant that we had plenty of condensation. We fortunately had our clothes in sealed plastic bags, but soon, with the combination of getting soaked on deck and condensation below deck, everything became damp, if not wet.

We believe nearly all crew crawled into their bunks with most of their clothes on – there was no room to change, and hopping around in a dangerously restricted space, just to get up a few hours later for your watch – well not such a good idea!

Lynne surfaced as the Faroe Islands came spectacularly into view, grateful for dinner at last in the cockpit, but it seemed an eternity to finally reach the marina in Klaksvik. She was looking forward to a motionless night on board, without the need to cling on. Fingers crossed things would start to improve!

We had all made it to The Faroe Islands, after a tough passage; the only casualty was a sparrow, we christened Spencer, who had hitched a lift. Spencer parked himself on the traveller swivel block for the first part of the passage, but was found the next day, while at deep ocean, between lashed sails on the foredeck. He was given an honourable burial at sea.

Sounds like a nightmareish start to the sail for Lynne. Not feeling envious!

Absolutely not for me!

Fortunately it got much better; back to my old self! I don’t know whether I should be disappointed with the pharmacist who recommended Kwells (as seasickness medication), because when I opened the packet, it stated quite categorically that they were not to be taken by the over-60’s without a doctor’s permission. I take meagre comfort that I don’t look my age!

I am usually always up for an adventure. But in this case …..

Well done, both of you